Think of the last time you didn’t want to eat dessert, then did anyway. You could have said, “No,” so why didn’t you?

More importantly, how do you make it so that you can deny the sweets next time?

This post answers those questions.

If you want the FREE e-book that breaks down willpower for fat loss, put your email here and I’ll send it to you.

Train the Brain

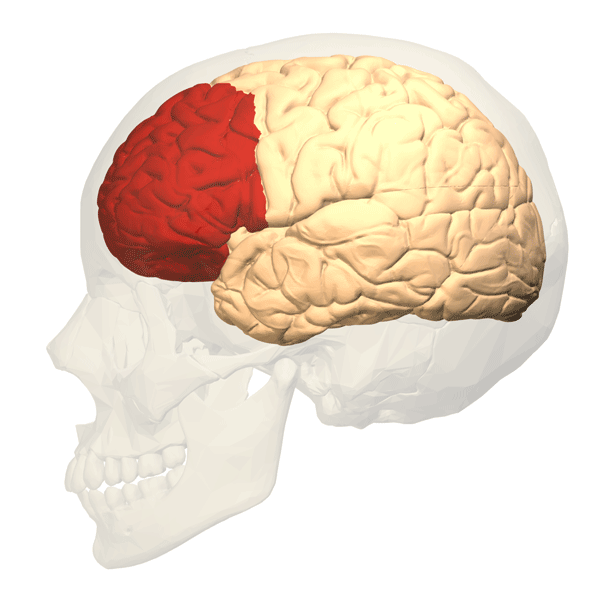

Many things contribute to a lack of willpower, but at the core of the problem is your wimpy prefrontal cortex. This area of the brain is largely responsible for self-control tasks like choosing to go to the gym, cooking dinner instead of microwaving it, and not sexually harassing the bank teller. The prefrontal cortex lets you make the more difficult decisions [1]; it makes the logical version of you. To increase willpower, we’re going to have to make this guy stronger.

Then, there’s another part of the brain which is full of emotion. This is responsible for your impulsive behavior. The emotional brain is fast and rash, while the logical brain is slow and calculated. And these two parts of the brain compete with each other.

When you decide to say, “Thank you,” and leave the bank instead of grabbing a handful of bank teller backside, your brain is fighting itself. The amygdala is screaming for inappropriate behavior, but the prefrontal cortex tells it to shut up [1]. The prefrontal cortex, your “voice of reason”, makes you less impulsive.

Emotional responses are easier default actions because they have become hardwired in your brain based on your past experiences. These responses are automatic. Doing the “harder” thing, a.k.a. exerting willpower, is so difficult because it requires conscious effort to suppress these urges.

If I’m learning how to do a new exercise, it starts out difficult and progressively gets easier. As I learn the task, my prefrontal cortex activity declines [1], and the movement progressively becomes more automatic. To keep training the prefrontal cortex, I need to keep learning new things.

If I played a lot of sports when I was younger, I have a ton of movement experience to draw upon. Learning new movements is easier now that I’m older because I can put the existing pieces together to build this new puzzle. Any personal trainer can validate the truth of this statement. It’s the difference between learning to ride a bike and riding a bike.

So, we use the prefrontal cortex in novel situations where our mental cruise control is not a viable option. How do we make these new behaviors stick? Create a craving for a reward.

The reward pathway of the brain is known to reinforce your behaviors, but this pathway doesn’t just respond to rewards, it also anticipates them. Part of this pathway points to the prefrontal cortex. This is good news because it allows us to reinforce good behaviors with proper rewards [1]. To do this, however, we need to understand what triggers our behaviors.

Know Thyself

The first rule of willpower, as Dr. Kelly McGonigal states in her book, The Willpower Instinct, is to “know thyself.” The key to knowing yourself is to develop a complete understanding of your habits.

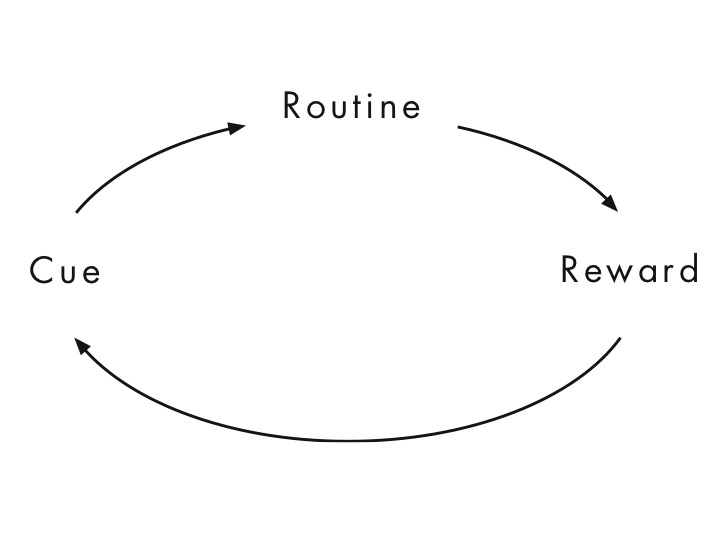

All of your behaviors have the same basic structure: something cues a routine you perform to obtain a reward. Charles Duhigg talks about this “habit loop” at length in his New York Times Bestseller, The Power of Habit (highly recommended).

Research also suggests willpower is like a muscle [2]. If a mentally-demanding task is spontaneously thrown upon you, you may not have enough willpower saved up to deal with it. Researchers call this loss of willpower “ego depletion“, using “ego” in the sense that Freud did years ago. That is, your higher cognitive functioning becomes depleted. This topic gets really interesting when you start to think about how this relates to a person’s degree of extroversion, like Susan Cain writes about in her book Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking. For example, going out to the bars rejuvenates some people (extroverts) and depletes others (introverts).

If you go through your past experiences, this strength model of self-control is pretty intuitive: it’s been a long day at work, you last ate at noon, and it takes you an hour and a half to get home due to traffic. When you finally walk through the door, you find some delicious, red velvet cupcakes topped with creamy, white frosting (Side note: this may have just happened to me two minutes ago). You grab the red glob of sweetness and collapse on the couch.

In the above scenario, your stressful work day, lack of food, and long commute have left you depleted. You don’t have enough willpower left to say, “You know, I better grill some salmon.” This is a prime example of subconsciously conserving your resources in case you need them for something really important later, like deciding on a plan of action when a felon plows through your front door in the middle of the night.

How do we turn this scenario around? We have to realize everything that’s in play.

Role Play: Dealing with Depletion

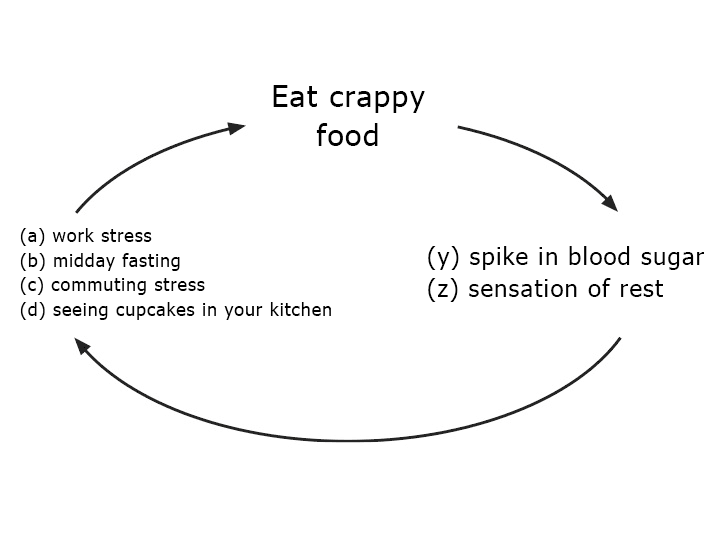

Let’s break down the habit loop of this situation:

- Cues: (a) work stress, (b) midday fasting, (c) commuting stress, and (d) seeing cupcakes in your kitchen

- Routine: eat crappy food

- Rewards: (y) spike in blood sugar and (z) sensation of rest

The first option is to head the problem off at the source by avoiding the cues entirely.

Why is (a) your job stressing you out? Maybe you can work something out with your boss, plan your work day ahead of time, or even find a new job if it has come to that.

Avoid (b) fasting by keeping a healthy snack in your desk that you can eat between meals.

Reduce (c) commuting stress by adjusting your schedule so that you miss rush hour, move closer to work, or take public transportation so you can get things done during your commute without having to focus on the road.

How did the (d) cupcakes get in your house? If it was you, stop making cupcakes. Simple as that. Don’t even buy the ingredients.

If it was your spouse, tell them these cupcakes make it very difficult to stay compliant with your health goals. Ask if there’s any way they could stop baking cupcakes. Or say goodbye and become single again.

If it was your lovely little sister and her boyfriend, crumble them up and pour them over her sleeping body while leaving a note from Brennan saying that he’s found another woman and moved on.

You don’t need boys, Madison.

My emotional brain may have taken over for a second. Logical brain… back online.

Removing the cue for unwanted behavior is an example of “shaping the path”, which I’ve talked about previously.

Now, sometimes it’s not possible to completely avoid the cues. In this case, substitute a new routine that gives you the same rewards.

One of the best ways to prevent unwanted behavior is by planning ahead [19]. This is why “know thyself” is the first rule of willpower: if you can anticipate future moments of weakness, you can play through the scenario in your mind and use your logical brain to make the right decision instead. Those who do not plan ahead let their emotional brain run the show in the heat of the moment.

Write down or record a memo detailing what you want to do when the time comes and it will be easier to stay on track. In this case, you still come home tired and hungry, but there’s another option besides the cupcakes because you already prepared a healthy snack. You still get (y) the spike in blood sugar, and (z) the sensation of rest.

Planning ahead works in situations other than just food preparation. If you anticipate a stressful day at work, maybe you schedule a short break every hour to take a walk around the office. Now your work day, overall, is less tiring.

What else can you do? Well, why don’t you ask your future self? Sure, that cupcake seems appealing to Present You, but Future You is going to be upset when she’s feeling sick and sleepy in a half hour, not to mention when she counts up her calories at the end of the day and realizes she went over because of that freaking sugar bomb. Picturing the future makes the consequences of your actions become real instead of just hypothetical.

Maybe you write a note to Future You. If Present You continues to sabotage Past You’s plans, Future You will never come into existence. Use a sticky note or www.futureme.org to become the Secret Service protection of your future self.

Forgot to Plan Ahead?

We talked about picturing your future self after she experiences the consequences of your bad decisions, but what if we frame it with positivity? Picture where you want to be instead of focusing on your bad behavior. Why do you have these goals in the first place? What will you be like when you’ve succeeded? Say hello to Skinny You. These are the reasons you’ve set goals for yourself. Remember that and it will be a lot easier to stay on track.

I often make my client draw a picture of him- or herself of what they will look like when they’ve accomplished their goal. I make them keep this with them at all times and look at it whenever they’re about to make a decision that is detrimental to their success.

Here’s another quick trick: Pull out your phone and open up a stopwatch app. Give it ten minutes. This gives your emotional brain time to quiet down. If you still want that crappy food after ten minutes of waiting, go for it. The reward system in your brain freaks out over immediate rewards, but the reaction diminishes if the cupcakes become a future reward—even if the future is only ten minutes away.

You can also learn to accept the urge to go off your diet without giving in. There was a study [23] where researchers gave subjects a box of Hershey’s Kisses to keep with them at all times. Two experimental groups were given advice on how to handle the urge to eat the chocolates.

The first group was told to distract themselves when they had the urge and argue with their feelings. “You don’t need any chocolate and you shouldn’t have any.”

The second group was told not to push away the urge. They were told to notice and accept their feelings, but realize that they did not have to act on those feelings. They were only asked to control their behavior, not their thoughts as well.

This acceptance-based strategy proved most effective for people who usually have the least amount of control around food. So, if food usually runs your life, try to accept your feelings before realizing you don’t have to act on them.

Someone please get these out of my kitchen.

Assuming you’re already on your way to changing a behavior, be sure to avoid the guilt trap when you stumble off the path. Muraven and colleagues [20] found that those who drank more than they wanted to ended up blowing past their goal and reported more guilty feelings about their night. Dr. McGonigal calls this the what-the-hell effect, where if you miss your goal, you say, “What the hell, I already blew it. I might as well go all out.” This effect has also been demonstrated in dieters who were told they weighed five pounds more than their actual weight: they feel less self-worth and eat more after the bad news [21].

Side note: a lot of the stuff in this post is from Dr. McGonigal’s book. I strongly suggest purchasing it if you’re the type of person who likes reading.

Positive affect also seems to help deal with depletion [22]. Theoretically, feel-good emotions give you optimism. This explains why getting someone to laugh makes them feel better. Even more beneficial is when you can make someone feel confident because they feel competent. Seeing actual progress is one of the best feelings we can experience.

Now that you know yourself, you can formulate a plan to accomplish your goals. But behavior change is hard, and all these little psychological tricks aren’t going to work forever. How can you make it easier?

Your Secret Weapon: Diet

Diet is a key player in willpower [4, 14-16].

Wang and Dvorak [16] compared the effects of Sprite and Sprite Zero on a subject’s ability to put off an immediate reward for a larger reward in the future. Those who had the Sprite with the fake sugar were less willing to wait for a bigger reward.

Since tasks that make you to think require energy, someone who doesn’t have available sugar is more prone to decreased willpower [15, 17]. This ties in nicely with the example I used above of coming home hungry: maybe you don’t have the energy resources (blood sugar or “glucose”) to make good decisions.

A Primer on Diabetes

To understand why having control over your diet is so important for increasing willpower, you need to understand how your body uses food. For those who don’t know, there are two types of diabetes: insipidus and mellitus. The former has to do with the body’s ability to reabsorb water in the blood and is not particularly pertinent to our current conversation. The latter describes the body’s inability to use sugar, which, as mentioned above, is an important energy source.

There are two types of diabetes mellitus. Type I people don’t produce insulin, the hormone which tells the body to take the sugar from the blood and store it in bodily tissues. The treatment for this is relatively simple: put more insulin in the blood when it’s needed.

Sometimes the body produces insulin, but the cells don’t respond. This is type II diabetes mellitus. These people are generally inactive and obese. In cases of type II diabetes, the dysfunction is not with insulin, but with the cells all over the body. These cells have been overstimulated time and time again, so they become desensitized to the release of insulin (like the boy who cried wolf). The signal is present, but the response is nowhere to be found. This situation is akin to being locked in a soundproof room filling with water: you scream at the top of your lungs, but nobody hears you.

Type II diabetes mellitus is most often what is meant when someone talks about diabetes because it is the most common form (90-95% of cases of diabetes mellitus are type II [29]). This can manifest with just a poor diet and lack of exercise.

The other reason it’s most often talked about is because it doesn’t happen overnight. The body’s cells gradually become resistant to insulin after it’s pumped out in mass quantities over and over and over again, which happens when sugar is regularly overconsumed. This means that most cases are preventable if we can stop the excessive release of insulin. Some people can even reverse their diagnosis of type II diabetes. Action step here: don’t abuse sugar.

What Does This Have to do with Willpower?

Now we might be inclined to say that more sugar in the blood is better. After all, that means we have more energy in the blood. But it isn’t that simple.

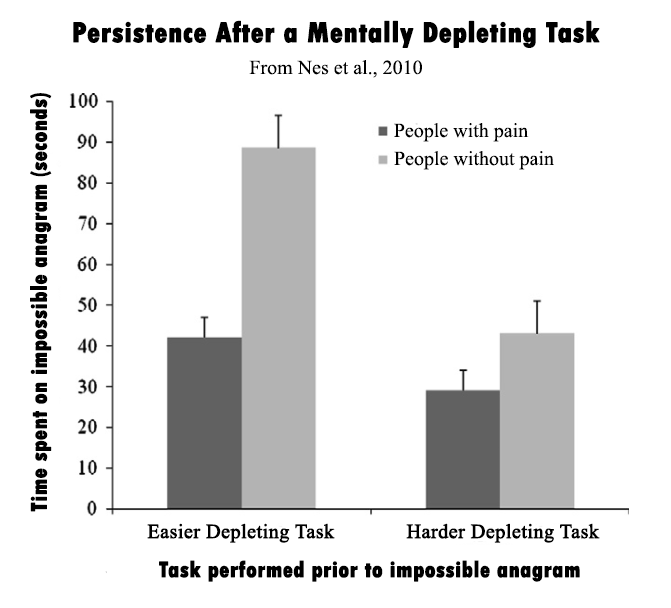

In fact, Nes and colleagues [4] found that those with lower blood sugar were more persistent in trying to solve an impossible anagram, while other studies [15, 16] said the opposite—those with higher blood glucose have more willpower.

How in the world can two groups of researchers look at the same thing and find the opposite results?

The caveat here is the age of the study participants.

Younger people haven’t had as much time for lots of insulin to be released, so we don’t see as many young people with diabetes as we see old people. Nes et al [4] had an average subject age in the 40s, while the other two studies used college undergraduates as their subjects. Presumably, the older subjects have more difficulty using glucose than the young subjects due to age and inactivity, just as we discussed a few paragraphs ago. Again, the key here is to not abuse sugar.

If I’m healthy, I may be able to find enough sugar to function well even if I haven’t eaten for hours because I can mobilize stored energy. If I’m unhealthy, I might have tons of glucose, but none available to be used because my cells are resistant to insulin. So the sugar stays in the blood and out of the places that need it.

We have established that sugar is necessary for willpower tasks [15, 17], and that sugar needs to be in the cells to be used. Some of those cells are brain cells. Do you remember which area of the brain is responsible for executive function? The prefrontal cortex. Make it so that you can use the sugar, and the prefrontal cortex has energy available to do its job and the logical version of You can come out.

So instead of having Golden Grahams every day, a breakfast cereal that spikes your insulin a lot, maybe you can have oatmeal or sweet potatoes after a workout. This way you take advantage of the insulin spike, putting nutrients into your muscles that are low on amino acids and sugar. You get fewer, smaller spikes of insulin, which keeps you sensitive to this precious, anabolic hormone. Insulin sensitivity leads to greater willpower.

But we’re not finished yet.

The Important Role of Exercise

Exercise helps the body use glucose [18]. And if the body can use glucose, then you have the energy for willpower. This loop reinforces itself, making behavior change progressively easier. You start to become a better version of yourself.

Compound age with busy schedules, joint pain, and the fear of what others think, and we have an explanation as to why more old people have diabetes than young people. Busy schedules lead to a perceived or actual lack of available time to exercise and eat well. Joint pain can be aggravated by exercise, so it is avoided. A lack of movement competence means less confidence when moving, so exercise is avoided for fear of embarrassment.

This becomes a huge problem because exercise is good for you. In the specific case of using sugar for energy, exercise puts in the pumps that help make insulin more effective. Insulin tells these pumps to move sugar into the cells, which gives our cells an energy source. If we have adults who are afraid to exercise, they are not optimizing their utilization of energy, and worse yet, nobody is setting a healthy example for our children. This is why I run a Youth Athletic Development class. Kids need to move.

Measuring Willpower

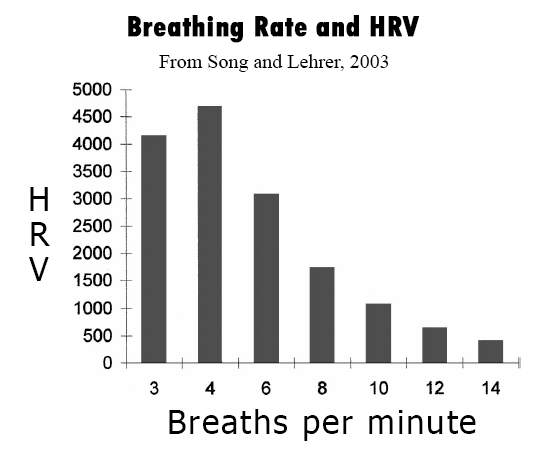

The coolest fact I’ve picked up about willpower is that it can be measured with technology that is readily available to the lay person: heart rate variability (HRV) [3-4].

HRV is the variation in time between heart beats. This variation is controlled by the two branches of the autonomic nervous system: sympathetic and parasympathetic. The sympathetic branch makes you alert and decreases variation (fight, flight, or freeze), while the parasympathetic relaxes you and increases variation (rest and digest). Tying in with what we learned about the brain above, sympathetic is the fast, emotional brain, and parasympathetic is the slow, logical brain.

There’s a guy by the name of Joel Jamieson who popularized HRV, making it easily accessible to the public via his system, BioForce HRV. This tool could help me with the first rule of willpower and give me a sense of my own HRV. That is, help me know myself. Heart rate is always fluctuating, but if I’ve been particularly stressed lately, whether that be from my job, sleep habits, or exercise, there will be less variation. It is, then, more likely that my emotional brain will hijack my logical brain’s executive function.

What do I do about this?

Well, to maximize willpower, I want to maximize HRV, so I had best be exercising.

- Get neutral to control your breathing [5] (see picture below).

- Make sure the aerobic system has the capacity to work [6-8] (think longer, continuous exercise that lowers your heart rate over the long-term).

- Make sure the aerobic system can turn on fast enough (think quick recovery from intense bouts like weight training [9, 10]).

There are studies that have directly measured exercise training and willpower [11-13]. Van Rensburg and colleagues [12] found that 15-minutes of moderate-intensity exercise decreased the craving to smoke in smokers who had been without nicotine for 15 hours. Ultimately, what this tells us is that even a little exercise is better than none. It’s not about setting world records, it’s about living an active lifestyle, so do whatever you have fun doing.

A Place to Begin

For more structured programming, start by taking your resting heart rate first thing in the morning. If that number is above 60 beats per minute for three consecutive days, you need to do some more aerobic exercise. Try out this quick interval circuit at least five days a week:

- 2-KB Front Squat

- Push Up

- Reverse Lunge (alternate legs)

- Split Stance Cable Row (left arm)

- Split Stance Cable Row (right arm)

- Dead Bug

Do exercise 1 for 45 seconds, then rest for 15 seconds. Do exercise 2 for 45 seconds, then rest for 15 seconds again. Go through all five exercises 6 times for a total of 30 rounds. The goal is to keep moving, so keep the weights light.

Re-check your resting heart rate every week. Once it is consistently below 60 beats per minute in the morning, you can add in some more intense exercise 3 times per week.

Where to Go Next

I always suggest having a plan of action when it comes to your training.

I strongly recommend that you hire a knowledgeable trainer who can write you a personalized program. This is a long-term solution to your health and fitness goals, making it the number one option. Coaches dedicate their lives to learning about this stuff and making their clients happy. When you think you’re sick, you go to the doctor. When you need help with exercise, you go to a trainer.

If, for whatever reason, that isn’t your cup of tea, I wrote up 4 months of workouts that you can find here.

The Bottom Line

The bottom line is that exercise is absolutely necessary, especially if you’re trying to lose weight. A study from Oaten and Cheng [11] looked at the effects of exercise on tons of factors over the course of two months. They found that exercise:

- Makes your willpower more resistant to fatigue.

- Reduces the need for pharmacological aids in the form of cigarettes, caffeine, alcohol.

- Increases self-reported healthy eating.

- Decreases many self-reported undesired behaviors (e.g. eating junk food, losing temper, procrastinating).

Exercise is an essential component of behavior change.

Pain is a Depleting Task

One thing I really wanted to touch on here is how chronic pain interacts with willpower. Essentially, chronic pain is a depleting task. Nes et al. [4] found those with fibromyalgia and/or jaw problems are less persistent than those who are pain free. In this study, the subjects were given an easy or difficult depleting task, then were asked to do an unsolvable anagram (where the letters of a word are all scrambled up). The researchers were looking to see how long the subjects would work before giving up. The figure below says it all.

This is why I want you to have a trainer who knows what they’re doing. It’s easy to give someone an exercise program that’s hard to do, but it’s difficult to give them something that will consistently make them better. These two things are not one in the same.

Sure, I can have un-athletic moms doing intense exercises for long durations, like box jumps, kipping pull ups, or whatever the workout of the day is, but not everyone can handle this type of training. When this reckless abandon catches up to you, you will feel tired, your joints will ache, and your motivation to train will plummet. Your ego will be depleted.

This is why you work on endurance before strength and power; you need to build up your body. If you go hard right off the bat, it catches up to you quickly. Adding variation into your training helps prevent overuse injuries and feeling burnt out. Ultimately, the only progress towards your goal that you can count is the progress that you can hold onto. Beating up your body isn’t going to keep you skinny if it makes you stop working out in a few months. Rome wasn’t built in a day.

Instead, look to make a lifestyle change. Create exercise habits that reinforce your healthy behaviors. This is a simple concept, but people everywhere fall in this trap. Let your training increase your willpower, not deplete it.

What’s Really Going on Here?

The other thing to realize is that if there really is a specific “resource” that is being depleted, these procedures do nothing to replenish that resource. In fact, they likely use even more of it. But just like with muscle, energy never reduces to zero.

Instead, the body stops you early so that you don’t die. What these tactics do is show your brain that it can survive even if it continues the task at hand. Laughing when you’re tired and need to find the willpower to make dinner serves the same purpose as a football coach’s “mental toughness” training: they’re both instances of gradual exposure to unfamiliar, potentially threatening stimuli.

What message are you sending your body?

Get Your Mind Right

The strength model of self-control ties in quite nicely with another book I highly recommend: Mindset by Carol Dweck.

The basic premise of Dweck’s book is that your qualities are only fixed if you think they are. She suggests discarding this “fixed mindset” for a more desirable “growth mindset” and becoming a lifelong learner. She’s basically me except way more intelligent.

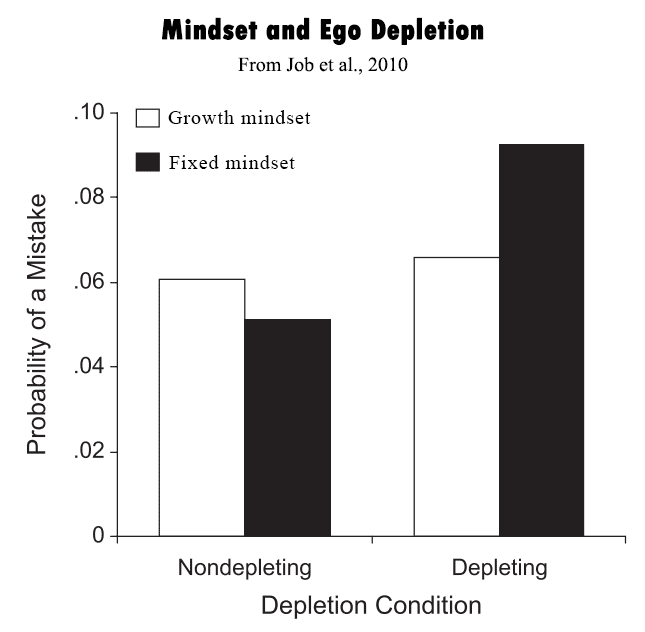

One of her published articles has combined her theory of mindset with ego depletion, proposing that you can only become depleted if you view willpower as something that is finite [24]. This suggests endless possibilities, at least in a developed area where things like famine and perpetual war are not issues.

To be clear, this isn’t suggesting everyone can be Usain Bolt. But can you run faster? You bet. Take the mindset research for what you will, but understanding that you can grow is liberating.

Summary

Knowing the inner workings of willpower is absolutely essential to health and fitness success. To reiterate at the expense of sounding like a broken record, exercise is the #1 starting point, allowing you to:

- Lose weight

- Eat better

- Set a positive example for your children

- Fight off future sickness

- Have more energy throughout the day to do the things you love

Hell, it will even help you do your laundry and clean the dishes [11].

Understand that your willpower is like a muscle. It turns on and off [25], can be trained [26], relies on diet [14-16], fatigues [17, 27], and you can magically find more energy if the stakes are high enough [28]. This hypothesis is the strength model of self-control [2].

Here are the 3 main points I want you to take away from this post:

- Exercise: hire a trainer or come up with an alternative plan.

- Know thyself: plan ahead, laugh, and picture the new person you’ll be next year.

- Eat well: see step 2.

I put together a free e-book showing how to use willpower to achieve your weight loss goals and help your clients achieve their goals.

If you want the FREE e-book, put your email here and I’ll send it to you.

P.S. If this article helped you, please share it with a friend who is looking for help changing their behavior.

For a related post from another author with good actionable steps, check out “You Don’t Need More Self-Discipline. You Need Nuclear Mode.” by Nate Green.

Photos courtesy of: Database Center for Life Science, Andrew Mason, april, Jill Brown, Thomas Tolkien, Allen Tucker, MarineCorps NewYork

Figures courtesy of Lance Goyke.

References

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). The frontal cortex and the criminal justice system. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 359(1451), 1787–96. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1547

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Tice DM. The Strength Model of Self-Control. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16(6):351–355.

- Segerstrom SC, Nes LS. Heart rate variability reflects self-regulatory strength, effort, and fatigue. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(3):275–81. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01888.x.

- Nes LS, Carlson CR, Crofford LJ, de Leeuw R, Segerstrom SC. Self-regulatory deficits in fibromyalgia and temporomandibular disorders. Pain. 2010;151(1):37–44. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.05.009.

- Song H-S, Lehrer PM. The effects of specific respiratory rates on heart rate and heart rate variability. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2003;28(1):13–23. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12737093.

- Levy WC, Cerqueira MD, Harp GD, et al. Effect of endurance exercise training on heart rate variability at rest in healthy young and older men. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(10):1236–41. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9832101. Accessed July 13, 2014.

- Lazoglu AH, Glace B, Gleim GW, Coplan NL. Exercise and heart rate variability. Am Heart J. 1996;131(4):825–6. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8721662.

- De Meersman RE. Heart rate variability and aerobic fitness. Am Heart J. 1993;125(3):726–31. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8438702.

- Figueroa A, Kingsley JD, McMillan V, Panton LB. Resistance exercise training improves heart rate variability in women with fibromyalgia. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2008;28(1):49–54. doi:10.1111/j.1475-097X.2007.00776.x.

- Camillo CA, Laburu VDM, Gonçalves NS, et al. Improvement of heart rate variability after exercise training and its predictors in COPD. Respir Med. 2011;105(7):1054–62. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2011.01.014.

- Oaten M, Cheng K. Longitudinal gains in self-regulation from regular physical exercise. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11(Pt 4):717–33. doi:10.1348/135910706X96481.

- Van Rensburg KJ, Taylor A, Hodgson T. The effects of acute exercise on attentional bias towards smoking-related stimuli during temporary abstinence from smoking. Addiction. 2009;104(11):1910–7. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02692.x.

- Hansen AL, Johnsen BH, Sollers JJ, Stenvik K, Thayer JF. Heart rate variability and its relation to prefrontal cognitive function: the effects of training and detraining. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;93(3):263–72. doi:10.1007/s00421-004-1208-0.

- Gailliot MT, Baumeister RF. The physiology of willpower: linking blood glucose to self-control. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2007;11(4):303–27. doi:10.1177/1088868307303030.

- Gailliot MT, Baumeister RF, DeWall CN, et al. Self-control relies on glucose as a limited energy source: willpower is more than a metaphor. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(2):325–36. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.325.

- Wang XT, Dvorak RD. Sweet future: fluctuating blood glucose levels affect future discounting. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(2):183–8. doi:10.1177/0956797609358096.

- Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Muraven M, Tice DM. Ego depletion: is the active self a limited resource? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(5):1252–65. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9599441.

- Ivy JL. Role of exercise training in the prevention and treatment of insulin resistance and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Sports Med. 1997;24(5):321–36. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9368278. Accessed July 14, 2014.

- Webb TL, Sheeran P. Can implementation intentions help to overcome ego-depletion? J Exp Soc Psychol. 2003;39(3):279–286. doi:10.1016/S0022-1031(02)00527-9.

- Muraven M, Collins RL, Morsheimer ET, Shiffman S, Paty JA. The morning after: limit violations and the self-regulation of alcohol consumption. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(3):253–62. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.253.

- McFarlane T, Polivy J, Herman CP. Effects of false weight feedback on mood, self-evaluation, and food intake in restrained and unrestrained eaters. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107(2):312–8. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9604560.

- Tice DM, Baumeister RF, Shmueli D, Muraven M. Restoring the self: Positive affect helps improve self-regulation following ego depletion. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2007;43(3):379–384. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2006.05.007.

- Forman EM, Hoffman KL, McGrath KB, Herbert JD, Brandsma LL, Lowe MR. A comparison of acceptance- and control-based strategies for coping with food cravings: an analog study. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(10):2372–86. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.004.

- Job V, Dweck CS, Walton GM. Ego depletion–is it all in your head? implicit theories about willpower affect self-regulation. Psychol Sci. 2010;21(11):1686–93. doi:10.1177/0956797610384745.

- Schmeichel BJ, Vohs KD, Baumeister RF. Intellectual performance and ego depletion: Role of the self in logical reasoning and other information processing. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(1):33–46. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.33.

- Baumeister RF, Gailliot M, DeWall CN, Oaten M. Self-regulation and personality: how interventions increase regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of traits on behavior. J Pers. 2006;74(6):1773–801. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00428.x.

- Richeson J a., Shelton JN. When Prejudice Does Not Pay: Effects of Interracial Contact on Executive Function. Psychol Sci. 2003;14(3):287–290. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.03437.

- Muraven M, Slessareva E. Mechanisms of self-control failure: motivation and limited resources. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29(7):894–906. doi:10.1177/0146167203029007008.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011.

Add some color to this commentary.