The short answer to this question is: “It depends.” The long answer is what follows.

Reasons you might change an exercise:

- There’s a better exercise you should be doing.

- You want to vary your training.

- To prevent boredom.

Reasons you might NOT change an exercise:

- You’re still seeing progress.

- It’s a very specific lift for your sport.

- It’s a fundamental movement (like a squat or a hip hinge).

Let’s break it down.

CHANGE: There’s a Better Exercise

This is the art of coaching. Being able to ebb and flow with the changing tides of training is a huge determinant of your success. I encounter this one all the time with my clients.

If I want someone to do split squats, but they just can’t maintain any semblance of good form, then it’s time to try a half kneeling cable chop instead. This is an example of an appropriate regression.

Now if I want someone to do a squatting bar reach to learn how to keep their pelvis underneath them, I might have their program written out for the next month, but if they get this down in a week, it’s time to move to a goblet squat. This is an example of an appropriate progression.

Play it by ear. If you’re training alone, use both objective (film yourself and watch the tape) and subjective (did that feel correct?) measurements of your progress.

CHANGE: Training Variation

The goal of training is to progressively adapt to stressful stimuli while maintaining the variability necessary to carry out any task you may need to perform.

“Progressively adapt to stressful stimuli,” means lose fat, put on muscle, and gain strength.

“Maintaining the variability necessary to carry out any task you may need to perform,” means don’t get hurt in the process.

So if I do the same exercises overandoverandoveragain, I get good at doing those exercises, but move me out of those exercises and I start to crumble.

My favorite way to maintain variability is to play games (like soccer tennis). If you need a more specific approach, you’re going to need to get a knowledgeable trainer or see a good physical therapist.

CHANGE: Prevent Boredom

Prevent boredom and you keep clients physically active. That’s one of the reasons you see my clients playing games during our group class or their own training.

This is an even bigger issue for kids. How can I accomplish what I need to accomplish while they have fun? Don’t criticize a child for not being interested in the squats you’re giving them. Instead, minimize the structure. Games are great for this, and as we just talked about, they’re also good for introducing variability.

Even simply loading an exercise in a different way, like holding the weights up high instead of down low, can keep someone interested in working out.

So now you know when to change your exercises, but when should you leave them alone?

DON’T CHANGE: Still Seeing Progress

This is the most obvious of reasons to keep something in your program. If the four weeks of your program are up, but the weights you’re using for your front squats are still rising, DON’T STOP. Ride those gains for as long as you can. Only then do you want to consider switching things up.

DON’T CHANGE: Specific for Your Sport

This one depends on where you are in your training cycle. The further out you are from a competition, the more “general” your exercises should be. This period is good for introducing variability.

If you’re eight weeks out from a powerlifting meet, however, you had best be squatting, benching, and deadlifting. You need to re-groove the patterns for those lifts.

If your sport is not a lifting-based one like powerlifting or Olympic lifting, you do the same thing, only different. If I’m a hammer thrower, I’m going to spend less time with a barbell and more time with a hammer. As I get closer and closer to competition day, I depart from “general” training and move toward more “specific” training.

DON’T CHANGE: Fundamental Movement Pattern

For every program, you want a bend, a squat, an upper body push, and an upper body pull.

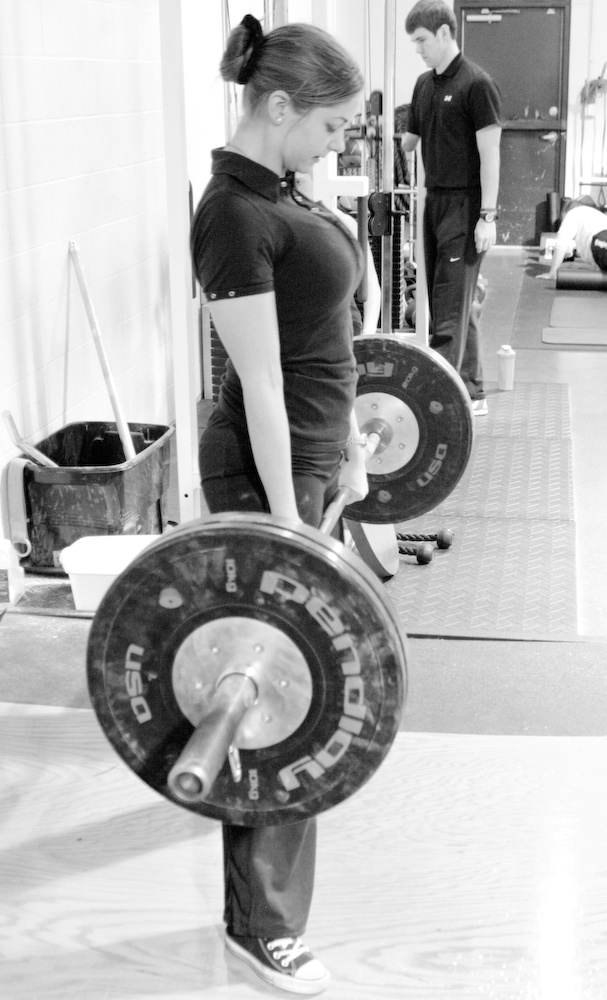

The bend, also known as a hip hinge, is any form of deadlift exercise. Examples include a Romanian deadlift, a rack pull, and a trap bar deadlift. These exercises teach my hips how to extend, and, performed correctly, are huge lifesavers on the low back throughout the day. If I only had one lower body exercise to load, it would be a bend pattern.

The squat is great for training knee extension. I may not choose to load the squat with a bar on my back, or maybe I won’t even load the squat at all, but this movement pattern is great for maintaining mobility across all joints. If nothing else, I can use a squat to train myself to control flexion across all joints, which is an essential trait if you want to maintain a high level of system variability.

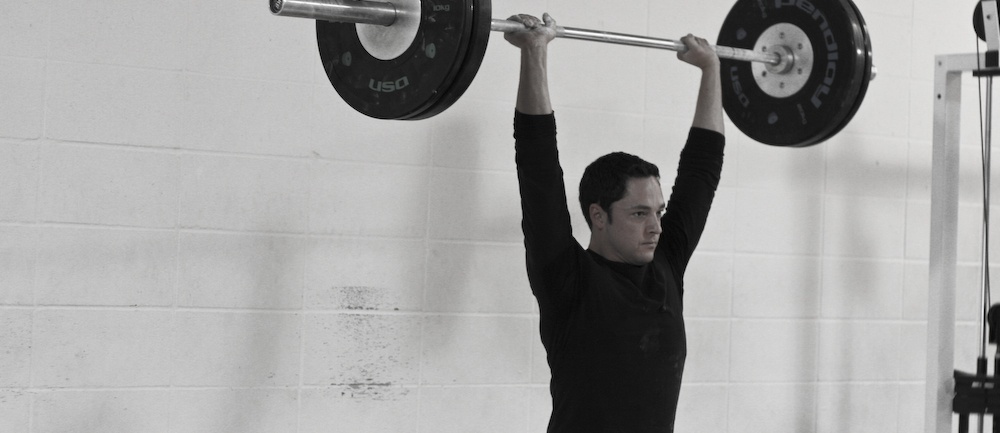

An upper body push can be horizontal or vertical. My favorite version is the push up, but bench presses, floor presses, landmine presses, and cable presses fit in there as well.

An upper body pull can also be horizontal or vertical. A one-arm dumbbell row stays in most of my programs, but cable rows, bent rows, and pull ups are also solid choices. Rowing exercises may be the first thing to go if I have a new client with shoulder issues.

End Note

Reasons you might change an exercise:

- There’s a better exercise you should be doing.

- You want to vary your training.

- To prevent boredom.

Reasons you might NOT change an exercise:

- You’re still seeing progress.

- It’s a very specific lift for your sport.

- It’s a fundamental movement (like a squat or a hip hinge).

If you still aren’t sure, you should hire a professional. If you don’t know how to work on cars, you wouldn’t try to fix one on your own. Why would you do it on the most important vehicle you will ever own?