Working out is about finding a balance. Train too hard and you break down, but don’t train hard enough and you won’t get anywhere.

Those who tend to train too hard are people I call “fitness junkies”. They usually enjoy Crossfit, screaming, and a burning sensation in their muscles.

Let’s talk about why you need some easy days if you really want to get strong.

Fitness Junkies Anonymous: How I Used to do Conditioning

Making progress in the gym is about busting your butt, so I used to figure that training hard ALL the time would be better than just SOME of the time.

Taking one week easy to “deload” every month was the most boring thing ever OH MY GAWD. It took every ounce of willpower I had to train easy on those weeks.

I couldn’t exercise enough. I loved being in the gym. That’s how I got into coaching.

More is better, right?

Well… not all the time.

The Downfall

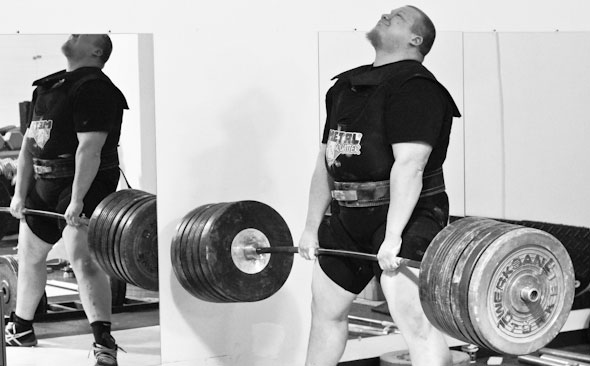

As my body got older, I gradually transitioned out of “getting euphoria from training” and into “getting pain from training”. This was highest during my days of powerlifting.

I remember the moment I realized it was a problem. My training partner and I were squatting. I set up with this huge arch in my back; I looked like a freaking archery bow. Every squat I did, I would feel pain in my hips. I had felt it before, but it wasn’t going away this time. I wasn’t going to be able to hit an adequately deep squat or lift any considerable weight at my next meet. At the end of each workout, I’d sprint a sled as fast as I could for 15 minutes.

All four of my training days each week were High/High/High/High intensity level.

And it was beating me up.

12-Step Program: What I Started Doing Differently

After I learned some new things, I changed my training a little, shifting away from lactic training and towards more alactic/aerobic and solely aerobic training. We’ll talk more about what those words mean here shortly.

There was a huge shift in how I felt once I started incorporating planned low-intensity training.

What is low-intensity training?

Intensity is a measure of how much weight you’re moving. When we say intensity, we’re referring to the intensity placed on your nervous system, which is primarily responsible for your gains in strength relative to your bodyweight.

So if I’m training with low intensity, I’m training with low weight.

Why would I want to train with low intensity if I want to get strong?

It seems counter-intuitive, right? If I want to move more weight, I should probably move more weight!

Yes, you want to move more weight, but you don’t have to do it more often. That was my biggest mistake.

You see, if you try to use as much weight as you can every training session (say you work out 4 times a week), then you will have have 4 training sessions with decently heavy weight, but you’ll never have the energy to break through a plateau.

But if you have low-intensity days that are supplemental and regenerative, then you can move some really heavy weight on your high-intensity days.

Think about it…

- There’s less overall shock for my joints and nervous system to deal with

- I start getting planned active recovery sessions to help my body regenerate

- I get a brain-refreshing change of pace from some novel training

- My high intensity days can be higher! (my deadlift went from 405lbs to 440lbs AFTER I stopped powerlifting)

Conditioning IS training

Now, it seems like I’m only talking about strength work, but I’m actually talking about ALL training. Even your conditioning has an element of intensity in it.

The best way to think about this is through the three systems of your body that produce energy: (a) alactic anaerobic, (b) lactic anaerobic, and (c) aerobic.

| (a) alactic anaerobic | (b) lactic anaerobic | (c) aerobic |

| Produces energy at a fast rate | Produces energy at a fast rate | Produces energy at a slower rate |

| Turns on immediately | Turns on almost immediately | Takes a while to turn on |

| Lasts for about 10 seconds | Lasts for about 2 minutes | Lasts for about forever |

| Does not use oxygen | Does not use oxygen | Requires oxygen |

| Used during high-intensity exercise | Used during high-intensity exercise | Used during low-intensity exercise |

| Causes fatigue to accumulate | Fights off fatigue | |

| Competes with the aerobic system | Competes with the lactic system | |

| Traditional alactic athlete example: 100m sprinter | Traditional lactic athlete example: 400m sprinter | Traditional aerobic athlete example: marathon runner |

| Least trainable | Most trainable |

The alactic and aerobic systems are actually really good partners. Team sport athletes (e.g. football, soccer, hockey) primarily use these two systems to beat their opponents.

For example, a football player goes really hard for a really short period of time, relying mostly on his alactic system. Then, during his rest period, he uses his aerobic system to recover from the play. He works very hard, but as long as he has a strong aerobic system, he doesn’t feel fatigue accumulate.

What does this mean to a fitness junkie?

I meet a lot of fitness junkies who like to stay in the lactic zone. They like to try really hard for really long periods of time and see if they can make themselves vomit. Or pee themselves. Or make their kidneys bleed. Or whatever.

There’s a place for some hard training, which we’ll discuss in the last section of this post, but if you want to improve your ability to recover (and you do, whether you know it or not), you need to incorporate some low-intensity training and some high/low training.

Take the football example and make it your own. Load up the sled with more weight than you usually do. Push it as fast as you can for 8 seconds, then stop and rest for 52 seconds. Then do it again 7 more times. There’s 8 minutes of alactic work with aerobic rest. This trains not only your alpha qualities (i.e. strength, speed-strength, power), but also your ability to recover. It teaches your aerobic system to turn on faster, helping you produce more energy with less fatigue.

Things You Can Try

Get a heart rate monitor and start testing yourself.

You’ll want to measure your resting heart rate, your heart rate recovery after a One Minute Go Test, and your 6-minute Modified Cooper Test. If you’re unfamiliar with those tests and training methods, see my post on How to Use a Heart Rate Monitor to learn how to do them, what they can tell you, and how to fine-tune your training.

- If your resting heart rate is 60 beats per minute or higher, do some cardiac output development 3-6 times a week for 30-90 minutes, keeping your heart rate between 120-150 beats per minute the entire time.

- If your heart rate doesn’t recover to 130 beats per minute within one minute after a One Minute Go Test, do some repeat sprints and high intensity continuous training.

- If your resting heart rate and heart rate recovery scores are good, try out some threshold training around your anaerobic threshold (which you found from your Modified Cooper Test).

- If your conditioning is great, do cardiac output development or high intensity continuous training as a planned recovery day 1-2 times per week.

Position Statement and Clarifications

I want to make it clear that I am not demonizing lactic training or working hard, neither am I suggesting that aerobic training is the secret to eternal wealth and power. I simply want to illustrate that they are different.

When I think lactic training, I think mental toughness and fatigue.

When I think aerobic training, I think recovery, energy development, and fatigue buffer.

Neither is bad, but aerobic adaptation is probably more useful for more people more often… especially those meatheads who train like I used to.

What are your goals?

- Performance?

- Health?

- Enjoyment?

If you’re training for performance, don’t listen to articles on the internet because they cannot be specific enough to optimize your training. Get a coach instead.

If you’re training for health, too much exercise is just as bad as too little exercise. You can still get stronger, but you’re not going to set world records if you prioritize health.

If you just want to have fun, then do whatever the hell makes you happy. If you need to throw up to feel like you got a good workout in, then throw up all you want.

Action Points

- Don’t try to train at maximum intensity every training session

- Do some conditioning tests

- Resting Heart Rate

- One Minute Go Test + Heart Rate Recovery

- 6 Minute Modified Cooper Test

- Do more cardiac output development

- 30-90 minutes with heart rate between 120-150 beats per minute

- Remember: more is not always better

- Do more repeated sprints

- 8 sec on : 52 sec off

- As hard/heavy/fast as possible

- 8 repeats

- What are you training for?

If you’re unclear on how to use a heart rate monitor, be sure to check out my other article on that topic.

Add some color to this commentary.