In preparation for the Postural Restoration Institute course I’m doing this weekend, I have been reading through some of the course’s references.

Today, I wanted to talk about one I just read that shows you why sensory information is so important.

Inglis, J. T., Horak, F. B., Shupert, C. L., & Jones-Rycewicz, C. (1994). The importance of somatosensory information in triggering and scaling automatic postural responses in humans. Experimental Brain Research, 101(1), 159–64. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7843295

This piece of work compared normal people to people who had lost feeling in both of their legs from having diabetes.

What they did was they had the subject stand on a piece of floor that was yanked out from under them. It moved 6cm backwards, causing a forward lean of their body relative to their feet. You can imagine how startling that might be. They wanted to see how these subjects responded to this postural sway. What they found was that people with less sensation in their lower legs:

- Take longer to respond to postural demands.

- Don’t respond as appropriately to postural demands when the ground moves faster.

- Don’t respond as appropriately to postural demands when the ground moves further.

Longer Response Time

These people might appear slower or take longer to get things done because they can’t gauge the demands placed upon them as quickly as those with full sensation.

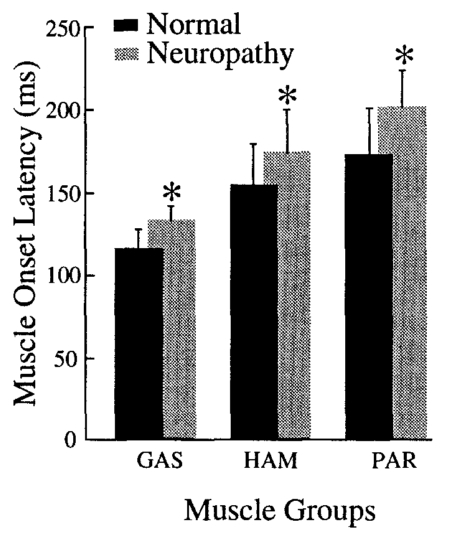

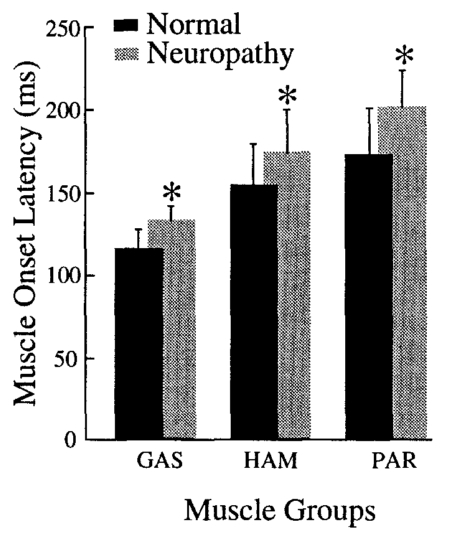

The figure below is a good visual of this finding. Each set of bars is a different muscle (three in total). The asterisk means the findings were statistically significant. The higher gray bars means it took more time for people with less sensation in their legs to respond to the moving floor.

Less Appropriate Postural Response

As the demand for adjusting posture increases, people with less sensation don’t respond to the same extent as those with normal sensation. If the floor moves out from under you slowly, you would react with less UMPH. The patients have more UMPH (they try harder). If the floor moves quicker, you would scale your response to be stronger. The patients don’t scale as well.

Think of this in terms of unpredictable slipping-and-falling accidents.

Now with respect to how far the ground moves out from under them, they tried harder than people with full sensation in their legs, but they didn’t adjust as well according to how far the platform was moving. These people were all over the place with their postural responses.

Also worth noting is that they produced higher forces, so muscular weakness is unlikely to be the cause of their postural response issues.

Interpretation

This is a simple study that shows the importance of sensory information. When we start talking about sensation, my brain immediately goes to the right foot.

Due to our asymmetries and our desire to stand on our right legs, the right foot turns outward (supinates). If it stays out there, then my right foot’s inside arch and big toe don’t get much sensory information.

Given this, it’s likely that their postural responses will not be as appropriate as someone who has “found” the floor. It’s not likely that they will fall, but they will have poorer responses.

These people might get tired more easily and react more slowly because they’re trying to hard and doing too much. Those muscles are freaking out when they don’t have to because their feet are telling them to do so.

Practicality

This is why we have to think about sensation when coaching. So if that right foot is rolling outward, tell them to stick it to the ground like a tree’s roots in the ground. Spread your toes out.

Just last night I had a client who showed this. She’s having trouble getting her right glute max to work when it should, and it makes her right knee hurt when she squats.

When I asked her to show me her squat, her toes start singing and dancing. As she squats down, the toes come up. Squat up, toes back down. It’s like I’m watching a game of Whack-A-Mole.

But when we cue her right arch to stay on the floor, her toes go down on both feet.

The sensation tells her feet that they can relaxxx. It also tell that to every other part of her body.

When you’re coaching someone, make sure you give the feet the respect they deserve.